Yesterday I met Gary Marsden, from the University of Capetown’s Computer Science department. Gary is one of the conference organisers for DIS 2008, which will be taking place in Cape Town just before Design Indaba, next February. The whole thing promises to be a really interesting chance to think about design in the context of tighter constraints than we’re used to in the western world.

Gary has been doing all sorts of interaction design experiments at UCT – some more successful than others. He’s also done a fair amount of ethnography about how technology is being used in rural Africa at the moment. Some of it has showed up on his blog and there’s a chapter about his ethno trip to Zambia at the end of his recent book. The theme of what he’s found: big expensive technology is no use at all in many parts of Africa. It’s small pieces of practical technology, carefully designed to fit in with the way people live and work, that end up being a success.

What follows is a very dramatic illustration of this.

Gary was kind enough to take me up to the university campus and show me round a bit. Gary’s department put together a rather cool VR ROOM – an experiment in building an immersive VR environment on something approaching an African budget. It’s in a very small, windowless room that was once, perhaps, a storage room. It’s been painted up and given nice lighting and carpet so it doesn’t feel like a closet. The room is divided completely in two by a giant perspex screen. The screen twists on a central hinge. When it’s “open,” you can see a collection of tech goodies hiding behind it. There’s a pair of ordinary data projectors, each with a hand-cut polarising filter bolted on, a nice hi-fi system, a plain-looking PC with a 3D graphics card or two in it and a fair few wires. Gary fires it up, you put on the ludicrous polarised specs and hey presto, you’re looking at a life size, 3D environment that almost fills your field of vision. I like it!

What do they use it for? Gary showed me two examples. The first was a virtual cave – an exact copy of one somewhere in Botswana. A particular tribe held this cave sacred and could only tell certain stories from their culture when standing inside it. The tribe have been relocated because of diamonds or tourism or some other excuse, so they no longer have access to the cave their culture is dying. The VR cave was intended to preserve their culture in the 21st Century.

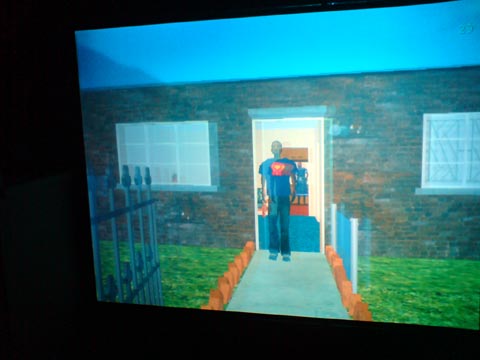

The second example was an interactive walkthough of a virtual house, intended to help educate people with HIV (and there are LOT in South Africa) about how to stay healthy and deal with the challenges the disease brings. The intention was to install this in AIDS clinics to help with education. You can have conversations with digital avatars that many people would find too embarrassing to have with a real person.

So. The Vrroom closet is a heap of fun and a really ingenious piece of technology. Gary’s team have learned a lot about creating a feeling of presence on a budget. But have the applications themselves have really been a hit? No. The pilot installation in an AIDS clinic was dismantled by thieves. And how can someone from Botswana who has never used a computer or even watched TV relate to a 3D virtual cave? They can’t. The technology is way too big – it doesn’t fit into your life, it wants to take over your life. And most of us aren’t quite ready for that grade of technological impact.

Gary is the first to discuss the failures, and like any good designer to extract the important lessons from them. He stresses the value of ethnography as a driver for successful innovation. To design for people in developing countries you have to understand how the culture works, what people do, how they communicate and what they really need. Don’t try to change people’s lives, try to fit in and make a small but important improvements. Ease of use is surprisingly unimportant in these contexts – usefulness is everything. People will adopt technologies if and only if they really make life better.

Gary is involved in growing the field of ICT for developing countries. It’s a small field now, but everyone tells us that the market is there for technology in the developing world, so it may grow in importance. Gary’s more recent projects are making big differences in small ways. Using mobile phones with picture messaging to help remote clinics diagnose difficult cases? A smash hit.

In developing countries, innovations that succeed match user needs and behaviours, and deliver real improvement to people’s quality of life. Is that so different from design in the Western World? No. It’s just the same. Only more so.